Working Paper 26: The ambivalence of social networks and their role in spurring and potential for curbing petty corruption: comparative insights from East Africa

This paper compares social network dynamics and related petty corrupt practices in East Africa. It highlights how the properties of structural and functional networks could serve as entry points for anti-corruption interventions.

With a focus on the health sector in Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, the empirical findings from this research corroborate the role of social networks in perpetuating collective practices of petty corruption, including bribery, favouritism and gift-giving.

The paper makes a case for designing a novel type of behavioural anti-corruption intervention, whereby the power of social networks is harnessed to elicit behavioural and attitudinal change for anti-corruption outcomes.

This paper is part of the Basel Institute on Governance Working Paper Series, ISSN: 2624-9650.

Links and other languages

Table of Contents

1.1 Traditional Approaches to Anti-Corruption and Rational Drivers of Corruption

1.2 Taking Account of Social Dynamics and their Role in Spurring Corruption

2 The Prevalence of Petty Corruption in East Africa and the Role of Social Networks

2.1 Prevalence of Petty Corruption in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda

2.2 Social Networks and their Structural and Functional Attributes

3 Structure and Functions of Informal Social Networks in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda

3.1 Network Structures, Social Norms and Enforcement Mechanisms

3.2 Social Networks Function as Problem-Solving Resources

3.3 Informal Practices of the Network Function to Increase Social Justice

4 The Ambivalent and Two-edged Nature of Social Networks as an Entry Point for Anti-Corruption

4.1 Ambivalence of Corrupt Behaviours

4.2 Social Networks are Two-Edged

4.3 Implications for Anti-Corruption

5 Network-Driven Anti-Corruption Interventions

5.1 The Adoption of Network-Driven Approaches from the Field of Behavioural Public Health

5.2 Critical Network Properties and Context Conditions

5.3 Avenues for Network-Driven Interventions in East Africa – a First Appraisal

5.4 Proposing a Logic Model and Theory of Change for Network-Driven Interventions

About the authors

Cosimo Stahl

Public Governance Specialist

Cosimo Stahl is a Public Governance Specialist with the Basel Institute on Governance in Switzerland. His work focuses on behavioural approaches to studying and combatting corruption. Cosimo is also pursuing a PhD at University College London, where he investigates the role and power of anti-corruption social movements in Latin America.

Saba Kassa

Public Governance Specialist

Saba Kassa is a Public Governance Specialist with the Basel Institute on Governance. She supports the Public Governance Division in the development and implementation of its various research and technical support projects. Saba holds a PhD in International Development Studies from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

1 Introduction – A Behavioural Social Network-Centred Approach to Anti-Corruption

1.1 Traditional Approaches to Anti-Corruption and Rational Drivers of Corruption

In light of overwhelming evidence of ineffective legal, institutional and organisational anti-corruption interventions (cf. Ledeneva et al., 2017; Marquette and Peiffer, 2015; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2011; Persson et al., 2013), we acquiesce in the call by many academics and anti-corruption practitioners to consider local contexts and realities for implementing more innovative anti-corruption interventions (Haruna, 2003; Mette Kjaer, 2004; Rugumyamheto, 2004). This requires for anti-corruption interventions to be sensitised to locally prevailing social habits, expectations as well as cultural understandings and attitudes vis-à-vis corruption (Baez-Camargo and Passas, 2017; Koni-Hoffmann and Navanit-Patel, 2017). In line with other authors (Ledeneva et al., 2017; Marquette and Peiffer, 2015), we argue that existing theoretical and conceptual models of corruption, which anti-corruption interventions are essentially based upon in terms of their programme design and theory of change, are not rivalling each other but should in fact be considered conjointly.

Following this line of thought, corruption may be both a cause and consequence of accountability problems due to imperfect asymmetric information between an agent and a principal, whereby lack of oversight and ineffective monitoring incentivises agents to engage in corruption (Klitgaard, 1988; Rose-Ackerman, 1978). Corruption may at the same time be fuelled by large-scale collective action and coordination problems whereby an individual’s decision to engage in corruption hinges upon their perception of their close environment as uncooperative and highly corrupt, thereby justifying their own corrupt behaviour on the basis of reciprocity and simply as ‘the way things are done’ (Marquette and Peiffer, 2015; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2011; Persson et al., 2013; also, Rothstein, 2013). Moreover, corruption may not necessarily constitute a problem per se but can actually offer pragmatic solutions to ordinary citizens as means of ‘getting things done’ (Marquette and Peiffer, 2015), while at the level of business and political elites it may fulfil informal governance functions critical for regime stability and survival (Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva, 2017). What these approaches have in common are institutionalist, structuralist or game-theoretical underpinnings based on micro-level rational choice assumptions of human decision-making from standard economics. Conventional anti-corruption interventions modelled on the theoretical underpinnings of the prominent principal/agent model have failed to produce sufficient favourable anti-corruption outcomes.

1.2 Taking Account of Social Dynamics and their Role in Spurring Corruption

Rather than following a ‘one-size-fits all’ approach aimed at implementing international anti-corruption ‘best practices’ from the Global North, we argue that anti-corruption interventions must be tailored to local realities in order to increase their likelihood for success. It is therefore necessary to empirically assess the socio-cultural environments and politico-economic contexts where anti-corruption interventions are to be implemented.

Contrary to some authors who merely assign socio-cultural traits to collective practices of corruption (Hodess et al., 2001; Rothstein, 2011, p. 231), we propose to extend the conceptual scope and include behavioural drivers of corruption, namely those socio-cultural determinants of certain types of corrupt behaviours and collective practices that have become normalised and routinised in contexts where corruption is endemic, systemic and has become the normal state of affairs (cf. Koni-Hoffmann and Navanit-Patel, 2017). We thus argue that certain corrupt behaviours have become a feature during the socialisation and enculturation of individuals (cf. Gavelek and Kong, 2012; Hoff and Stiglitz, 2015). As a result, they have grown to be socially embedded, culturally rooted and mentally engrained in the form of local social norms, collective imaginaries and vernacular knowledge.

The difference of this fourth perspective lies in that social dynamics at the community-level undergird the collective reproduction of certain corrupt practices at the hands of individuals who are at the same time members of a multitude of social networks. In such a community setting, fixed preferences at the micro-level may become endogenous; in other words, rational cost-benefit calculations of individual network members can, on the one hand, be overridden by socio-cultural commands and group expectations in certain socio-cultural contexts. This is the case when people feel compelled to engage in corruption against their better judgement, out of a sense of moral obligation towards the group, to meet community expectations, to either gain social rewards or to avoid social punishments for not complying with informal and unwritten norms and practices. On the other hand, aspiring to be part of social networks may be the rational and pragmatic thing to do as network membership often comes with ‘perks’ insofar as remedy is provided to network members in contexts of resource scarcity and service delivery underperformance. In such a case, the benefits derived from said network membership outweigh the costs, or in other words, the aforementioned network commands and group expectations. In either case, both micro-level preferences and cost-benefit calculations of individual network member are endogenous – as they are attributable to the individual members’ exposure to a given cultural context (‘mental models’) and social fabric (‘sociality’). This socio-cultural environment is shaped by a plethora of social network dynamics and the different sets of social rules, expectations and beliefs they form and generate. Thus, central are elements of sociality and collective ways of thinking (‘mental models’) and their role as, what we have previously labelled, behavioural drivers of corruption (Baez-Camargo, 2017; Stahl et al., 2017).[1] At the very core of this fourth approach lie social interactions and relationships of social exchange in community settings expressed in the form of said social network dynamics.

This paper sheds light upon these social network dynamics and their problematic role in spurring petty corruption in the health sector in the East African context, with a focus on day-to-day interactions between ordinary citizens and service seekers on one side, and low-to-mid level officials and service providers on the other. It also makes explicit the inherently ambivalent nature of social networks by laying bare the attitudes and motivations of network members, as well as the costs attached with network membership. By distinguishing between structural and functional properties, social network dynamics that account for the collective reproduction of network-prescribed petty corrupt practices are causally explained. Empirical evidence is drawn from qualitative research conducted in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda in 2016 and 2017.[2] Whilst controlling for national contexts and local realities, a comparison of these three countries - which vary significantly in terms of corruption prevalence, scale and propensity despite sharing comparable socio-cultural norms and practices – allows for the illustration of how social networks can also be potentially harnessed for favourable anti-corruption and social policy outcomes.

2 The Prevalence of Petty Corruption in East Africa and the Role of Social Networks

2.1 Prevalence of Petty Corruption in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda

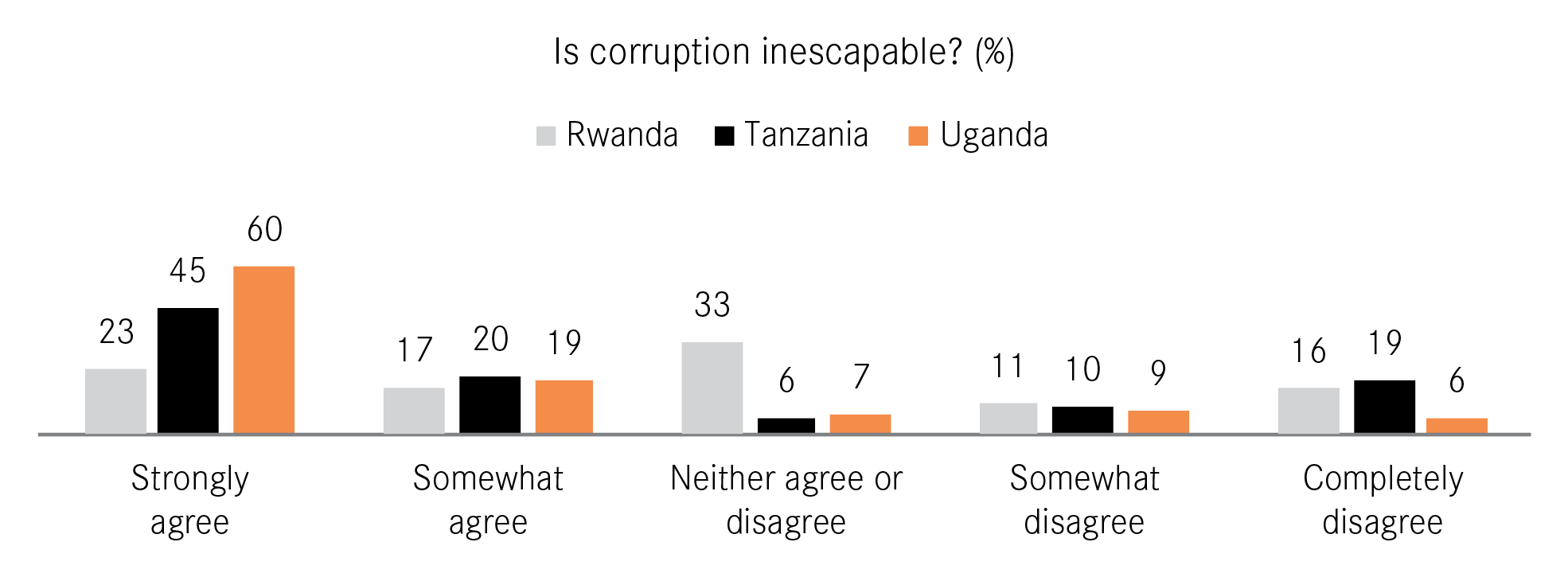

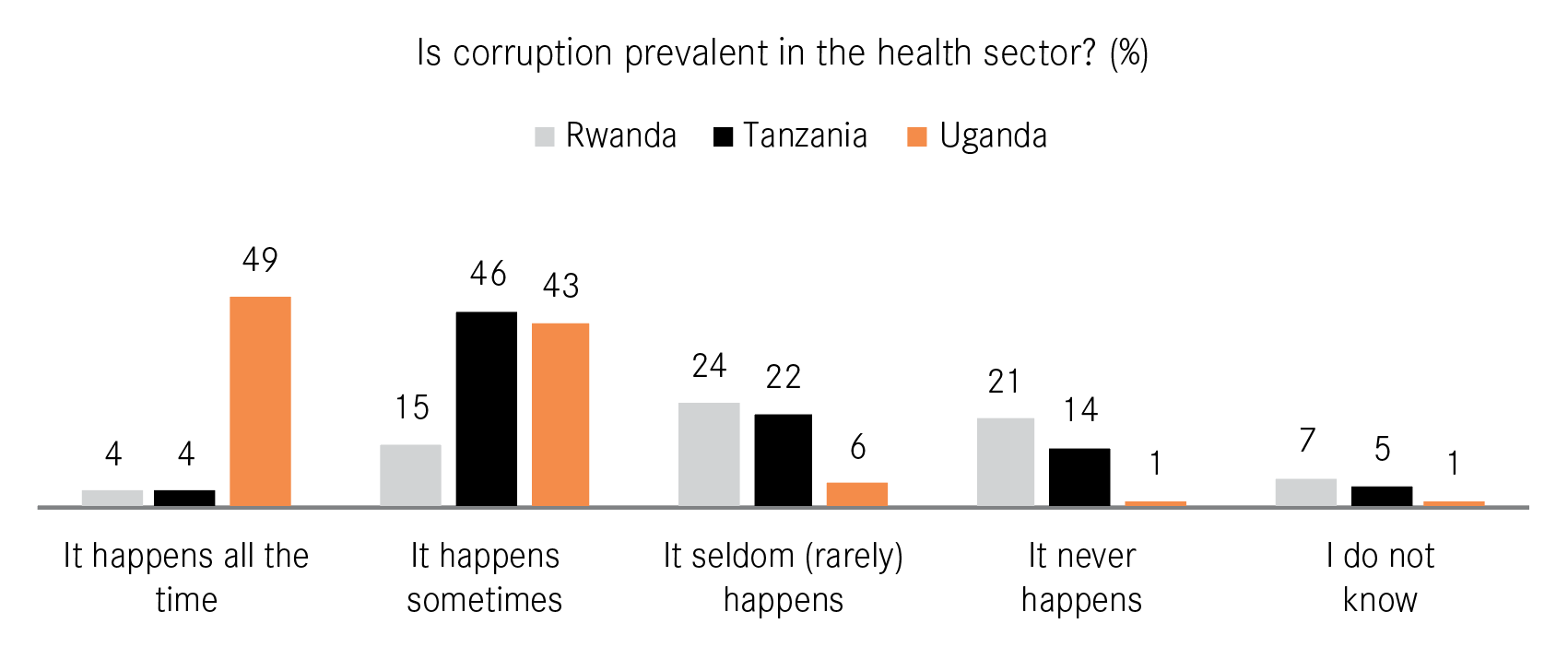

The research showcases that practices of petty corruption are present in the health sector in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda, albeit to different degrees. In Uganda, where anti-corruption efforts under President Museveni continue to bear rather modest effects, petty corrupt practices are most widespread and have become endemic and normalised. In Tanzania, which out of the three countries analysed and among African countries can be considered a middle-performer, petty corruption has been declining as a result of renewed anti-corruption efforts and bold actions taken by the administration of President John Magufuli. In Rwanda, a country considered to be one of the anti-corruption success stories and top performers in Africa, practices associated with petty corruption that are found in neighbouring Tanzania and Uganda are far less common, mostly due the zero-tolerance approach to corruption led by President Paul Kagame, which is not only characterised by harsh punishment and a strict law enforcement policy but also entails large-scale awareness raising campaigns aimed at sensitising the Rwandan public about the value of anti-corruption and integrity. These trends are corroborated by the latest international assessments, recent national corruption surveys and our own research (Figure 1).

The encounters between citizens and providers of health services are shaped by these broader patterns associated with the prevalence of petty corruption. In Uganda and to a lesser extent in Tanzania, research participants shared that bribery, favouritism (and gift-giving) or a combination of both are commonly encountered when accessing health services. This is very different in Rwanda, where services are mostly provided as mandated by the rules and regulations governing the public provision of health services in that country. These patterns and trends are also captured in the survey results below (Figure 2).

A crucial observation is that the provision of health services is not regulated by formal rights and entitlements that de iure govern the provision of public services but instead on the basis of informal social network relationships and dynamics between service seekers on one side and health service providers on the other. In both Tanzania and Uganda, social networks reproduce petty corrupt practices, although to differing degrees. One of the implications is that for medical treatment to be facilitated, it matters if the service user has some kind of relationship with the health provider and/or if the person can afford to pay a bribe. While the scale of petty corruption and the forms it takes differ across the three countries, the influence of social dynamics and relational networks is actually found in all of them, thereby, illustrating the resilience of socially-driven corrupt behaviours. In other words, petty and/or silent corruption and associated practices – including bribery, favouritisms, absenteeism and gift-giving – may be governed by sociality and in fact be a product of social dynamics and network relations.

2.2 Social Networks and their Structural and Functional Attributes

A social network is simply defined as a network or group of people characterised by social ties and patterns of social interactions which make up the structure of a network (cf. Newman, 2010, Chapter 1, p.6). This means that a specific social network may be structured by distinct social ties and prescribe specific social relationships and interactions that characterise the pattern of social organisation within said network. Therefore, there may be different levels of social organisation within and between social networks depending on the type of social ties and the prescribed social interactions. In a given social system such as a society (or a social subsystem, such as a community), the structure of social networks thus affects the behaviours prescribed, the functions performed, and the type of social influence exerted on individual decision-making. A major driver of social influence is social support, and social networks themselves can be conceptualised as sources of different types of social support (Latkin and Knowlton, 2015, p. 5). The distinction is made between structural and functional support with the former referring to the extent of network connectedness and social integration (for example, the type and number of social ties) and the latter comprising the specific social network functions provided (Wills and Shinar, 2000).[3] We henceforth distinguish between structural and functional network attributes or properties. Thus, the former are those attributes and properties that ‘make up a network’, the latter refer to what networks ‘deliver’.

This can be illustrated with the following example: we have learnt that across the three countries social network connections matter greatly but to different extents. In the health sectors of Uganda and Tanzania, social networks provide pragmatic means to an end as they constitute a crucial safety net in the light of economic hardship and institutional inefficacy. As such, service seekers resort to their social networks to secure medical treatment. In Rwanda, although resorting to social networks to get treatment is not necessary, social networks play a pivotal part in Rwandan society and are highly valued. Being part of a social network comes with strings as it is almost a cultural imperative to give into network demands. This generates a great deal of conflict and distress among Rwandan service providers as they feel compelled to give preferential treatment to their respective network peers.

In the three countries studied, social proximity is a key structural attribute and key criterion for the type of connection and strength of social ties between network members that determines the nature of a network in terms of the function it fulfils, and the behaviours prescribed. Depending on the strength of social bond/tie, social networks may indeed fulfil different functions. For example, close family members are bound by the obligation to share and contribute to group welfare which results in public officials being expected to divert resources for the benefit of the network. More distant acquaintances relate to each other on the basis of reciprocity: for a favour (for example, preferential treatment) received, one feels indebted and bound to return said favour at some point (for example, by giving a gift). In all three countries, social networks of family and friends make up the most closely knit and strongest networks, albeit to different degrees in terms of the functions fulfilled and behaviours prescribed. The most prevalent are networks of family and friends, that are structured by social ties based on kinship, friendship, solidarity and loyalty - but in each county the social interactions endorsed, or in other words, deemed acceptable and unacceptable do indeed, vary.

In Rwanda, where social networks of family are bound by strong social ties based on primordial notions of kinship, solidarity and loyalty - family relations and close friendships are collectively praised the most. Therefore, helping a family member or close friend out in their moments of need is an imperative, to such an extent that the petty corrupt practice of favouritism among health care providers persists and is even perpetuated, despite the high repercussions and severe punishments one could face. Family and friendship networks in Rwanda simultaneously fulfil social and pragmatic functions.

In Tanzania, social networks are not constrained to close family, kinship and very close friendship ties like in Rwanda, but slightly more loosely defined but still strong enough to provide an informal rule book prescribing practices associated with petty corruption. For example, for bribery and favouritism in the health sector to occur, it is usually necessary that the involving parties are either distantly related to each other, or have been acquainted with each other by a ‘mutual friend’ acting as a middle man. For example, a friend may introduce his relative who needs urgent health care to a friend and service provider willing to grant preferential treatment in exchange for a ‘little something’. Thus, in Tanzania social networks are defined a little more loosely in terms of social proximity and they fulfil an inherently pragmatic function in the health sector.

In Uganda, where corruption is virtually everywhere, networks of family and friends themselves are not necessarily void of corruption as they are rather weakly defined among younger Ugandans. Older research participants who appraise social networks more strongly, repeatedly lament the fact that nowadays, a family or friendship tie would not necessarily shield one from falling victim to within-network corruption and would not guarantee the informal provision of a public service. While social networks can still be a source of social support and fulfil both social and pragmatic functions, it is not only kinship and friendship that determines the strength and functions of networks, but apparently also the age of network members and their respective individual personal agendas and incentives. For older Ugandans, family networks should provide both pragmatic means and instil solidarity, whereas for some younger Ugandans, they seem to play a rather pragmatic role up to the point where within-network corruption is seen as a source of extra income for some.

Other structural network properties regulating the extent of network connectedness are socio-economic variables, such as age, social status and standing.[4] Furthermore, there are certain primordial cultural values and social norms, such as kinship loyalty, communal solidarity, culturally mandated reciprocity and obligation to contribute group welfare that govern the social organisation and relationships of networks – including the rules of informal social exchange. The latter are engrained in local socio-cultural structures and collective ways of thinking which are associated with social values and cultural imperatives. Following Hoff and Stiglitz (2015), these could be labelled socio-cultural determinants of human decision-making, or in this case, corrupt behaviour.

As subsequently illustrated in the next sections discussing the empirical evidence, the research indeed shows that social networks comprise both structural and functional attributes. These network properties may motivate and induce individuals to join and be part of a network in the first place. We will showcase how social network properties have a significant influence on the provision of health services in East Africa. One could argue that the fact that an entire social system, such as a society, is highly affected by corruption may be attributable to the prevailing structures of different social networks within said society. In such case, the network-prescribed social interactions and relationships that govern corrupt transactions in the public sector, such as the health sector, may have become routinised and normalised. In the eyes of many, the functional nature of social networks and the ends at which they aim justify the means. Arguably, this may account for an increase in tolerability and social acceptability of corruption. This is to show how the aforementioned network dynamics may indeed perpetuate corruption by means of collectivisation of associated corrupt practices. The good news is, as we shall argue, is that social networks are potentially powerful anti-corruption tools, if steered and harnessed for favourable anti-corruption outcomes.

3 Structure and Functions of Informal Social Networks in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda

3.1 Network Structures, Social Norms and Enforcement Mechanisms

As previously denoted, social proximity is thus a key structural property that governs the working of social networks. The research takes note of two groups that are characterised by a high social proximity between them: the first is the family, which is considered to be the most important and trusted social group of relations. Friends and acquaintances make up the second most significant social network group. Informal networks can also be constructed on the basis of more specific criteria of group affiliation, such as gender, ethnicity or religion. Moreover, social networks can also be found at the workplace, such as horizontally between colleagues and vertically between superiors and frontline officers. It is significant that all these relations are found not to be static, but rather fluid and at times even instrumental, whereby networks develop on the basis of ‘relatives of friends’ and ‘friend of friends’. This fluidity of network membership criteria means that even kinship ties can be manipulated instrumentally and opportunistically as evidenced from research on social networks in Kyrgyzstan (Aksana, 2018: 12).

Furthermore, the social networks observed in the research are strongly underpinned by social values and norms that shape and give meaning to each particular interaction. A crucial social norm is found with regards to family relations as research participants agree that sharing with your next of kin and contributing to group welfare is socially commanded. In practice, this means that family members are expected to take care and support each other, which is considered an ‘essential, unquestionable premise of social life in the three countries’. In the context of service provision, the prominent value given to family and kinship accounts for stringent expectations towards single family members who hold a public-sector job and who are expected to use the access to resources stemming from their positions for the benefit of the family. This is vividly explained by a health sector district official in Tanzania who commented: “it’s not that we have a lot of money to help five or six relatives, but […] whatever you get you share with others.” Another service provider complemented this assertion by explaining the underlying principle as follows: “you will help that person because it’s your blood.” Health facility staff in Kampala similarly shared the expectation that family always comes first by explaining that “your relative must be given priority if there is not an emergency, my mother, father, son or daughter come first.” The importance of strong family ties can translate into common proverbs as exemplified in Rwanda: utagira nyirasenge arisenga [whoever does not have an aunt slips in isolation] or urukwavu rukuze rwonka abana [the old rabbit is taken care of by its children]. The social expectation that members of the network should share their income and resources with each other encourages practices of favouritism in the provision of health services. These pressures on the public service provider can be so stringent that in cases when the salary is considered insufficient to satisfy the additional needs of the network, it may necessitate the provider to use more extortive modalities such as bribing or embezzlement in the practice of the office. The implication is that the degree of network proximity becomes a strong determinant of the quality of treatment received.

With regards to the core networks composed of friends and other acquaintances, another important social norm or value observed is the obligation to reciprocate gifts and favours received. These engagements reflect more of a transaction-based relationship of indebtedness and entitlement between the giver and receiver of services. A research participant in Tanzania explains this logic as follows: “There is a reciprocal relationship meaning today you have helped me, so tomorrow I must find a way to return the favour.” When such social norms on reciprocity are transposed to the public service, it translates into practices of gift-giving and bribery because services rendered are seen as favours rather than entitlements. For instance, the duty to honour one’s debt justifies the behaviour of service providers when they request “takrima” (a favour or hospitality) for services provided in the case of Tanzania. Similarly, in Rwanda, research participants share that bribes are more likely to occur in instances where the service provider and user are friends. These transactions involving a favour or a gift can be replicated and sustained through time as evidenced in the case of Uganda.

All network members aim to adhere to these social norms and values as they are reinforced by means of social rules and controls associated with status and respect. This means for instance that a service provider that rejects a gift offered by a user is considered disrespectful in the Ugandan context. In Tanzania, research participants share that service providers that consistently fail to provide preferential treatment to relatives will destroy their social standing. Likewise, in Rwanda, research participants explain that such a bad reputation can even “travel” and as a consequence the service provider involved might lose friends and be scorned by extended family members. A research participant from Kigali succinctly explains this as follows: “No one can ignore the importance [that] Rwandan people attach to relationships and [there are] consequences associated with not serving the neighbour or one of your family members, even when the situation does not allow [you to do so].” Group expectations and obligations are thus collectively reinforced by means of peer pressure, social sanctions and morally upheld by informal rules of reciprocity and kinship solidarity. In the African context, reciprocity is considered to be socio-culturally anchored in tribal affinity, pre-colonial community values and associated with social norms of more collectivist societies (Blundo and Olivier de Sardan, 2006; Ekeh, 1975; Sardan, 1999). The entrenchment of these norms is evident in the case of Rwanda, where in spite of the strict legal enforcement of anti-corruption laws, individuals still feel bound by social obligations.

In sum, social proximity (sociality) and the socio-cultural norms and values of communal solidarity and group welfare as a common good, as well as culturally mandated reciprocity and mutual obligation, and lastly social status and respect could all be summarised under the umbrella term of structural network properties as they characterise the make-up and workings of social networks.

3.2 Social Networks Function as Problem-Solving Resources

Social networks are valued and preeminent when they represent problem-solving resources. The primary functional attribute of the network is their use as informal social safety nets on which members can rely on in order to access public health services. While social networks have this instrumental role across the three countries, the manner in which this is exercised depends on the accessibility of health services. The consensus among research participants in Uganda and Tanzania is that while health services are governed by formal rights and entitlements, in practice it is very difficult to exercise these provisions. In contrast, in Rwanda, research participants share that health services are provided according to the formal legal stipulations. Consequently, in Uganda and Tanzania, citizens often rely on their social network to obtain access to health services and consider this the only way to “get things done”. In this context of constrained access to health services, research participants in Kampala view favouritism in the health service not as corruption or bribery but simply as “using one’s networks and connections to get what one wants.” Similarly, in Tanzania, the research informs that service providers can even ask friends for bribes. This is seen as something normal as it simply concerns a fee to receive a quicker service. Thus, bribing has an instrumental intent and offers ordinary citizens ways in which they can solve the problems they face when accessing services. Therefore, citizens resort to their social network in an effort to obtain a “simplified” service delivery by for instance relying on or establishing a personal connection with a service provider to receive preferential treatment and exchanging a bribe or a gift to make the transaction a fair one. The situation is different in the case of Rwanda where social networks can be used to expedite health services but this form of favouritism is mostly circumscribed to family members and close friends only.

The functional attributes of the social network invoke that members find it is useful to build and extend it. Viewed this way, social networks represent a form of social capital that its members can rely on through the bonds that bind one another in the network. Expanding the network is achievable by creating personal links and relationships with the service provider based on bribes and gifts as is noted in Uganda and Tanzania. In Uganda, the research evidence shows that bribing is understood as a way in which a citizen can create a relationship with a service provider. This informal action co-opts the official into the personal network of the bribe giver. Extending the network beyond the family in the context of Tanzania involves developing relationships on the basis of reciprocity, whereby gifts can be used as a way to establish a personal link to the provider. This investment in the public official comes with the expectation and prospect of receiving future priority services. Even more strategic efforts entail the practice of developing personal connections with powerful and high-ranking persons. An illustrative example comes from Rwanda, where research participants share that district authorities or ranking officers of law enforcement agencies sometimes obtain preferential treatment at public health facilities. While on the one hand this can be interpreted as showing respect for the authority, it can also be associated with the desire to build a personal relationship with these influential persons as explained by the participant: “this favour towards authority may yield some benefit in the future, you never know!”.

Thus, social networks function as informal social safety nets that help cope with resource scarcity and consequently drives citizens to further extend it. The network-prescribed practices have a significant exponential effect as the logic of reciprocating bribes, gifts and favours received represent a cycle of being entitled to something or indebted to someone; thereby resulting in the continuation of corrupt practices. Moreover, such practices favour those that are part of the ‘in-group’ or have the financial means to build up the necessary network, which, in the cases of Uganda and Tanzania, ultimately account for a regressive health service.

3.3 Informal Practices of the Network Function to Increase Social Justice

The informal practices of the network are justified because they increase social justice among members. Communal and group solidarity is a powerful form of social currency that network members can resort to, because strong social ties reduce uncertainty and increase the ability to access health services. Consequently, a major transgression of this form of social justice occurs when members are considered to be indifferent to the needs of their network. An example of this is acting out of greed – such as demanding a bribe in a desperate situation (i.e. refusing to treat a person that is in critical condition) or requesting an unreasonably high bribe. Bribes motivated by this kind of greedy behaviour are understood as not sharing with the group in the context of Uganda. Similarly, in Tanzania, it is considered important to act with generosity. Continuously asking for bribes is considered selfish behaviour that stands in stark contrast with the communitarian beneficial purpose.

The implication is that social justice follows from behaviours by which members show compassion and solidarity with one another, particularly, when problems are resolved and/or resources are acquired to be shared among network members. These ideas are intimately tied to attitudes of tolerability and social acceptability of corrupt behaviours. Consequently, research participants In Kampala explain that the consequences of engaging in corrupt acts are: “to get very rich and wealthy and hence admired by the masses”, “to be popular, a celebrity and [thus] respected” and to “become an investor and employ other people”. Likewise, in Tanzania, the research evidence suggests that service providers that are open to receiving bribes or gifts or extend preferential treatment pleases people as explained by a participant as follows: “society will love him and even recommend people to him for fast services and “people will try to build good relationships with him and he would be respected and gain prestige.” This is also closely associated with social status as the service provider is acting with compassion and sharing

and supporting members of their network. Being recommended across networks can potentially create many informal clients and consequently increase the official’s social status, power and supplement low salaries. Nevertheless, service providers also express concerns about the overwhelming responsibilities and expectations that come with network membership.

Thus, the research indicates that citizens rely on family, friends and other extended relations as a pragmatic way to access health services and accordingly aim to build strategic new social relationships. The informal practices associated with the networks are justified because they promote social justice and fulfil the communitarian values of solidarity and fairness. It is these functional drivers, namely, the pragmatic ends they fulfil and the manner in which these are morally evaluated as being just associated with the social networks that spur the propensity of individuals to engage in corruption.

4 The Ambivalent and Two-Edged Nature of Social Networks as an Entry Point for Anti-Corruption

4.1 Ambivalence of Corrupt Behaviours

It is the structural and functional network properties that as key sources of social support spur collective practices of petty corruption in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda. This is a direct result of informal social dynamics which penetrate the seemingly ‘formal’ space of the public sector. The consequence of the superposition of informal rules and expectations over formal entitlements endows the behaviours of citizens and public officials alike with a great deal of ambivalence. Ambivalence arises when the formal rules dictating the provision of health services based on official qualifications and entitlements clash with social network expectations that are guided by more personalistic criteria. This distance between the formal and social normative frameworks leads to decision-making based on double standards where, often, it is considered more important to give into the needs of the network rather than abiding by the formal rules and duties of the office. This is morally justified because the research evidence suggests that the legal rules are viewed as unjust, whereas, network-based reciprocity promotes social fairness. The gap between these standards is most significant in Uganda and Tanzania. The fact that helping family or friends is considered a way of promoting social fairness in contrast to adhering to the formal rules of the office further adds to this ambivalence. This results in significant pressures and expectations being placed on public service officials to ensure that benefits are secured for the network. In the particular case of Tanzania, the stricter anti-corruption law enforcement under the new administration further complicates network-induced corrupt exchange, as the discretionary space to give into social demands is decreasing. Service providers testify that it is becoming very difficult to meet social expectations. Thus, while on the one hand networks perform crucial functional roles as informal social safety nets and promote social justice among its members, it simultaneously locks all the members in ever expanding social responsibilities. Interestingly, it is the Rwandan case which shows how this tension in the formality-informality gap can be addressed and even harnessed in favour of better anti-corruption outcomes.

4.2 Social Networks are Two-Edged

Contrary to Uganda and Tanzania, practices of petty corruption in Rwanda are much more limited and mainly exhibited in the form of favouritism among family members. This achievement can be attributed to the government’s holistic approach towards anti-corruption; focusing on the legal framework and the adoption of programmes that formalise social practices of community welfare. In regards to the former, the government has adopted a zero-tolerance approach to anti-corruption; the law is enforced and individuals caught face harsh punishments. This is complemented by an important behavioural component; following a corruption conviction, the names of corrupt perpetrators are publicised, alongside the names of their parents and communities of origin (“naming and shaming” approach). Various monitoring and evaluation strategies accompany this legal approach and aim to improve the quality and reduce opportunities for corruption in the public service. The research evidence shows that these sanctions are credible as research participants inform that bad performance is regularly detected and punished. The government also relies on more specific policy strategies for curbing petty corruption in the health sector, such as electronic queuing systems and the establishment of quality assurance and customer care units in health facilities.

The Home Grown Solutions is the umbrella term for all those “made in Rwanda” policies and programmes that incorporate traditional values into formal government strategies. These social policies include important behavioural anchors that aim to restore national identity and the notion of ‘Rwandanness’ in order to revive traditional values of integrity and honesty. The Ubudehe social programme categorises citizens by

income level, thereby providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable groups to access health services. Virtues associated with being a ‘good Rwandan’ are promoted through the Imihigo performance contracts, which comprise annual goals set for each community, whereby over-performers including the community of origin are socially and monetarily rewarded. Values of anti-corruption and integrity are fostered through Itorero and Ingando; the permanent schools for the promotion of a culture of excellence. Social justice, accountability and integrity norms instilled through these programmes are further reinforced via environmental cues, including the public display of codes of conduct and messages that confirm desirable behaviours in pursuit of the public good.

The research evidence from Rwanda shows that while social networks may offer resources to their members, relying on them can be risky as being caught engaging in corrupt actions can have grave implications for the entire network. This suggests that social networks can also help reduce corruption by reconstructing the notion of what it means to take care of each other (namely by not engaging in corrupt actions) and consequently redefining social status on the basis of integrity and actions that promote the public good.

4.3 Implications for Anti-Corruption

The three countries show considerable variation in terms of anti-corruption institutions and mechanisms set in place as well as the prevailing socio-economic context conditions which influence state and institutional efficacy and service delivery performance. The Rwandan case demonstrates that strong and credible anti-corruption oversight and monitoring institutions play a significant role in deterring corrupt behaviour, as incentives of both service seekers and providers are shaped to a great extent by a fear of legal punishments but also social repercussions. Furthermore, the comparison reasserts that attitudes and the proclivities vis-à-vis corruption are partly determined by socio-economic precariousness and negligent public service performance which drives highly pragmatic individuals to strategically engage in corruption to ‘get things done’. In Rwanda, the local populace does not have to find creative ways to access public services as they are accessible for all and smoothly provided, thereby critically reducing the functional value. Indeed, in cases where the state is not able to provide quality and easily accessible public services– bribery, favouritism and gift-giving fulfil a crucial pragmatic function. This is the case in Uganda – and, to a lesser extent in Tanzania, where petty corruption has become an essential feature of day-to-day transactions in public service delivery and highly pragmatic individuals justify their individual corrupt behaviour as they perceive corruption to be the default norm.

The research shows that peer pressure and group expectations of the network can in fact override individual incentives given by the formal rules especially, as the imposed social costs outweigh personal benefits. The social considerations are also predominant when there is weak enforceability of the formal rules, as Rwanda and the changing situation in Tanzania illustrate. Both of these factors account for the collective reproduction of social practices and norms of petty corruption. Nevertheless, Rwanda and increasingly Tanzania illustrate that increased oversight goes a long way in curtailing the prevalence of petty corruption associated with social networks. Moreover, insights from Rwanda give a first glance at the double-edged nature of informal social networks and how they can be utilised as policy entry-points for anti-corruption. Precisely this important role networks have in the lives of citizens makes them critical to be considered for designing innovative anti-corruption interventions.

5 Network-Driven Anti-Corruption Interventions

5.1 The Adoption of Network-Driven Approaches from the Field of Behavioural Public Health

In behavioural science, community-level behavioural change can be achieved by following different social influence strategies. This hinges on the intervention’s main goals, the problem to be tackled given a certain context, and the postulated underlying theoretical assumptions for programme change to attain such goals. Such an intervention may seek to change individual-level perceptions and attitudes, community-level behaviours and practices, and/or attempt to reach as many individuals from the population as possible. While the latter is mostly achieved through mass educational and media campaigns, the former two strategies rely predominantly on peer pressure (cf. Palluck, 2012; 2016). A network-driven intervention thus stipulates the power of peer influence and has two main tenets that can lead to positive anti-corruption outcomes: social diffusion (to disseminate information and new attitudinal and behavioural trends), and social norms change. Experimental research from the field of behavioural public health has indeed documented sustained behavioural effects of network-driven interventions (Latkin and Knowlton, 2015).[5]

Roughly speaking, there are two main types of network or ‘peer-driven’ interventions: (1) an ‘egocentric’ network-driven intervention, which seeks to tackle a specific high-risk behaviour among a strategically relevant personal network of closely-knit individuals as the target population; and (2) interventions of ‘sociometric’ networks, defined as a set of individuals bound together by specific ties in a given setting, where the target population is more loosely defined. Both intervention types harness the power of social ties and rely on social referents with social credentials – peer educators, community opinion leaders, or trendsetters – to act as agents of change. They differ in that the first type targets sharing rituals and collective norms of reciprocity that stir a network-prescribed behaviour or practice of high risk, mainly by reducing functionality.[6] At the core of such interventions lie the social organisation and regulation of said practices in contexts where the network provides critical practical and emotional support to balance hardship by means of communal solidarity and socio-economic exchange.[7] The second type of sociometric network-driven intervention seeks to change behavioural climates and patterns following one or a combination of the following strategies: 1) social diffusion through behavioural spill-overs and cascade effects, whereby critical information and even critical products (for example, medicines) are disseminated and behavioural trends emulated and adopted; or/and 2) social norms change.[8]

For example, an egocentric anti-corruption campaign could tackle the high-risk corruption practices perpetuated by vertical informal networks of corruption at the workplace. In Uganda, health care providers feel compelled to succumb to peer pressure exerted by vertically and hierarchically organised corruption networks at health care facilities. Peer pressure including social stigmatisation on one side and economic hardship on the other often drive individual health care providers to participate in the corruption schemes dictated by these networks, whereby almost all health workers and providers engage in collusive behaviours. Network members derive a functional and practical value from their membership as they gain direct economic and/or material benefits. Informal rules, including rewards for compliance and punishments for non-compliance, regulate this type of socio-economic exchange based on reciprocity, group rank and discipline. While simultaneously reducing the functionality of corruption by means of institutional and organisational reforms, an egocentric intervention could be aimed at singling out mid- to high-level members of such network and peers, who are willing to break with these corruption schemes and rituals, and convince fellow members to ‘change their ways’ by raising awareness of the detriments of corruption and diffusing new attitudes and behaviours for emulation.

A sociometric anti-corruption campaign on the other hand would encompass targeting a broader target population, for example a whole community, and diffuse critical information and new normative trends in the same manner through well respected community members of high social standing. In this case, no particular high-risk corrupt practice is targeted exclusively within an informal network that prescribes and reproduces such practices, but corruption is publicised more generally, again by means of diffusing critical anti-corruption information and setting more integer behavioural attitudes and trends. Unlike an egocentric intervention, the communal and social network properties are used for geometric recruitment whereby more trendsetters, opinion leaders and social referents are mobilised to further ‘spread the word’ and reach as many community members as possible.

Before designing a network-driven intervention, we need to understand how sociality, namely social influences, processes and organisations, promote behavioural trends and how aspects of social support, exchange and influence could be utilised to sustain behavioural change. Our study has yielded important insights into network inventories, including locally-specific factors and critical context conditions that are linked to positive and negative anti-corruption outcomes. Furthermore, we have been able to gather critical information about structural and functional network properties that tell us something about the stability and frequency of network-prescribed interactions (notably, the strength of social ties, the type and level of social support provided and the potential for within-network interpersonal conflict).

5.2 Critical Network Properties and Context Conditions

Network properties that are critical include social norms of reciprocity, which are prevalent in the three countries. Reciprocity is not only a source of strain and ambivalence – but directly facilitates corrupt exchange, whereby a vicious circle of corruption is reinforced. It is here where conventional anti-corruption efforts and reforms are essentially undermined by the ‘negative-feedback loops’ diffused among ordinary citizens. The root problems to be addressed are not only faulty collective action out of ‘rational irrationality’ (cf. Cassidy, 2009),[9] but also enculturated aspects of sociality and social norms themselves. A network-driven intervention could work through social norms of reciprocity by diffusing positive feedback and new normative attitudes. This could lead the way to promoting change in conventional wisdoms of corruption, reassessing the value and consequences of certain socio-cultural practices and ultimately decreasing their functionality. We have seen that context matters, whereby a network-driven intervention is more likely to provide remedy in contexts where a minimum degree of state efficacy and institutional oversight are given. Otherwise, corruption will continue to fulfil its highly pragmatic function.

Social networks should be stable, as more static network structures are more likely to lead to cooperation and much needed interaction between key co-operators, such as social referents (Rand et al., 2014). Low social trust and within-network corruption are indicative of instability of networks. One key indicator is social proximity and the type of social tie that sustains a network. The fluid character of some social networks may generally pose a problem as illustrated by the Ugandan case, where even the closest network of relatives and close friends is susceptible to uncooperative behaviour and within-network corruption. The Ugandan case also illustrates how socio-cultural values of ostentation (for example, among younger Ugandans) can lead to interpersonal conflicts that actually destroy social networks. A social influence strategy involving social referents acting as peer educators, opinion leaders and trendsetters requires for said referents to have social credentials and to enjoy a minimum of social trust vested in them by fellow network members.

5.3 Avenues for Network-Driven Interventions in East Africa – a First Appraisal

Context conditions, as well as network properties and factors are most favourable in Rwanda and Tanzania – given the crucial changes in their government’s anti-corruption approaches and efforts and a higher degree of network stability. This has opened a window of opportunity for behavioural interventions to be tested. In the case of Rwanda, where petty corruption has taken on a secretive and clandestine character given the harsh punishments and monitoring tools set in place, a network-driven intervention could be designed to eradicate high-risk behaviour of favouritism and gift-giving among health workers and their personal networks of relatives and close friends. In Tanzania, on the other hand a socio-metric network intervention aimed at changing the social acceptability of corruption could be an option, while seeking to change conventional wisdoms of petty corrupt practices based on notions of reciprocity.

Following this line of reasoning, a network-driven intervention may be more challenging to implement in Uganda, where corruption as a social norm has reached endemic levels. Furthermore, social networks are rather fluid and therefore more prone to within-network corruption and more susceptible to free rider, collective action and coordination problems. The aforementioned vertically organised corruption networks could constitute a promising avenue for an egocentric peer-driven intervention in Uganda, provided they are accompanied by efforts to reduce economic hardship in the country.

5.4 Proposing a Logic Model and Theory of Change for Network-Driven Interventions

The discussion above points to the centrality of influential and highly connected individuals to act as social referents who can promote the diffusion of critical information, as well as new normative and behavioural trends. For that matter, we propose to follow an “ITMC logic model” presupposing the following theory of change:

- During the ‘inception’ phase (I), the local context and the prevalence of network factors is assessed, including the type and nature of locally prevailing social networks that are associated with petty corruption. At this stage, it is of utmost importance to assess the extent and degree of social proximity governing the different types of social networks in existence, and evaluate the leverage and strength of prevailing social norms and cultural values one could play on in the scope of the intervention.

- During the ‘trendsetting’ stage (T), anti-corruption champions actively diffuse information that challenges conventional wisdoms about corruption, clarify the detriment of corruption at the expense of communities, and set new attitudinal and behavioural trends to be emulated. At this stage, social referents of high social standing enjoying a fair degree of network interconnected and social trust have been singled out.

- During the third stage (M for ‘mobilisation’), more allies convinced of the anti-corruption cause are ‘mobilised’ and geometrically recruited (beginning from a single seed) from within the social network to further spread the word and diffuse new behavioural trends. Anti-corruption success stories are publicised at this point, spreading the feeling that change is indeed possible.

- During stage four (C for actionable ‘change’), the new attitudinal and behavioural trends translate into large scale behavioural change at the community level. Ideally, actionable changes that come with successful reforms are palpable and almost celebrated at this stage, significantly improving the livelihoods of many.

6 Concluding remarks

Pragmatic motivations and socio-cultural norms are drivers related to social networks that spur the propensity of individuals to engage in collective practices of petty corruption – including bribery, favouritism and gift-giving. Most importantly, peer expectations and social network demands, but also cultural values and social norms, such as reciprocity, mutual obligation and group welfare, social status and respect are network attributes that structure the functioning and working of social network dynamics, including the perpetuation of the aforementioned corruption practices. While networks fulfil both pragmatic and social functions, these practices related to social networks are inherently ambivalent in nature. This is to mean, that if adequately steered and harnessed, the very attributes that grease these dynamics can be utilised for favourable anti-corruption outcomes. This is showcased by the case study of Rwanda, where corrupt perpetrators are publicly shunned by means of ‘naming and shaming’ and where integer and solidary behaviour is socially rewarded. Accordingly, we propose that social networks can also be harnessed to elicit behavioural and attitudinal change for favourable anti-corruption outcomes. In particular, contextual preconditions and crucial network properties should be considered when designing behavioural anti-corruption intervention. An ‘old’ key lesson learnt from this critical assessment is that anti-corruption interventions, conventional or behavioural, are highly context-dependent. This suggests that intervention designs and their underlying theory of programme change should be realistic, feasible and most importantly tailored to local needs and circumstances. The postulated network-centred approach to anti-corruption presents interesting avenues for further (experimental) research.

Bibliography

Aksana, I. 2018. Informal Governance and Corruption –Transcending the Principal Agent and Collective Action Paradigms Kyrgyzstan Country Report. Part 1 Macro Level. Basel Institute on Governance, Basel.

Baez-Camargo, C., 2017. Can a Behavioural Approach Help Fight Corruption? (Policy Brief No. 1). Basel Institute on Governance, Basel.

Baez-Camargo, C., Ledeneva, A., 2017. Where Does Informality Stop and Corruption Begin? Informal Governance and the Public/Private Crossover in Mexico, Russia and Tanzania. Slavon. East Eur. Rev. 95, 49–75.

Baez-Camargo, C., Passas, N., 2017. Hidden agendas, social norms and why we need to re-think anti-corruption (No. Working Paper No 22). Basel Institute on Governance, Basel.

Bicchieri, C., 2017. Norms in the wild: how to diagnose, measure, and change social norms / Cristina Bicchieri., Oxford scholarship online Y. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Blundo, G., Olivier de Sardan, J., 2006. Everyday Corruption and the State: citizens and public officials in Africa. Zed Books, London and New York.

Broadhead, R.S., Heckathorn, D.D., Weakliem, D.L., Anthony, D.L., Madray, H., Mills, R.J., Hughes, J., 1998. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 113, 42–57.

Cassidy, J., 2009. Rational Irrationality. New Yorker.

Ekeh, P.P., 1975. Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 17, 91–112.

Gavelek, J.R., Kong, D.A., 2012. Learning: A Process of Enculturation, in: Seel, P.D.N.M. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer US, pp. 2029–2032.

Haruna, P.F., 2003. Reforming Ghana’s Public Service: Issues and Experiences in Comparative Perspective. Public Adm. Rev. 63, 343–354.

Hodess, R., Banfield, J., Wolfe, T., 2001. Global Corruption Report 2001 - a TI publication. Transparency International, Berlin.

Hoff, K., Stiglitz, J.E., 2015. Striving for Balance in Economics: Towards a Theory of the Social Determination of Behavior (NBER Working Paper No. 21823). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Kim, D.A., Hwong, A.R., Stafford, D., Hughes, D.A., O’Malley, A.J., Fowler, J.H., Christakis, N.A., 2015. Social network targeting to maximise population behaviour change: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 386, 145–153.

Klitgaard, R., 1988. Controlling Corruption. University of California Press.

Koni-Hoffmann, L., Navanit-Patel, R., 2017. Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria: A Social Norms Approach to Connecting Society and Institutions. Chatham House - The Royal Institute of International Affairs, London.

Latkin, C.A., Knowlton, A.R., 2015. Social Network Assessments and Interventions for Health Behavior Change: A Critical Review. Behav. Med. Wash. DC 41, 90–97.

Ledeneva, A., Bratu, R., Köker, P., 2017. Corruption Studies for the Twenty-First Century: Paradigm Shifts and Innovative Approaches. Slavon. East Eur. Rev. 95, 1–20.

Mackie, G., Moneti, F., Shakya, H., Denny, E., 2015. What are social norms? How are they measured? UNICEF/University of California.

Mani, A., Rahwan, I., Pentland, A., 2013. Inducing Peer Pressure to Promote Cooperation. Sci. Rep. 3, 1735.

Marquette, H., Peiffer, C., 2015. Corruption and Collective Action (Research Paper No. 32), Developmental Leadership Program (DLP). University of Bermingham, Birmingham.

Mette Kjaer, A., 2004. An overview of rulers and public sector reforms in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. J. Mod. Afr.

Stud. 42, 389–413.

Mitchell, M.M., Robinson, A.C., Wolff, J., Knowlton, A.R., 2014. Perceived Mental Health Status of Injection Drug Users Living with HIV/AIDS: Concordance between Informal HIV Caregivers and Care Recipient Self-Reports and Associations with Caregiving Burden and Reciprocity. AIDS Behav. 18, 1103–1113.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A., 2011. Contextual Choices in Fighting Corruption: Lessons Learned (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2042021). Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY.

Paluck, E.L., 2009. What’s in a norm? Sources and processes of norm change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 594–600.

Paluck, E.L., Shepherd, H., 2012. The salience of social referents: a field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 899–915.

Paluck, E.L., Shepherd, H., Aronow, P.M., 2016. Changing climates of conflict: A social network experiment in 56 schools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 566–571.

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., Teorell, J., 2013. Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail—Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem. Governance 26, 449–471.

Rand, D.G., Nowak, M.A., Fowler, J.H., Christakis, N.A., 2014. Static network structure can stabilize human cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 17093–17098.

Rose-Ackerman, S., 1978. Corruption: a study in political economy. Academic Press, New York; London.

Rothstein, B., 2013. Corruption and Social Trust: Why the Fish Rots from the Head Down. Soc. Res. 80, 1009–1032.

Rothstein, B., 2011. Anti-corruption: the indirect ‘big bang’ approach. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 18, 228–250.

Rugumyamheto, J.A., 2004. Innovative approaches to reforming public services in Tanzania. Public Adm. Dev. 24, 437–446.

Sardan, J.P.O. de, 1999. A Moral Economy of Corruption in Africa? J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 37, 25–52.

Stahl, C., Kassa, S., Baez-Camargo, C., 2017. Drivers of Petty Corruption and Anti-Corruption Interventions in the Developing World - A semi-Systematic Review. Basel Institute on Governance, Basel.

Wills, T.A., Shinar, O., 2000. Measuring Perceived and Received Social Support, in: Gottlieb, B.H., Gordon, L.U., Cohen, S., Fetzer Institute (Eds.), Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 87–136.

[1] The World Bank’s 2015 World Development Report proposes three broad principles of human decision-making: automatic thinking, social thinking and thinking with mental models.

[2] The empirical findings stem from DFID-funded research on ‘Corruption, Social Norms and Behaviours in East Africa’. A qualitative comparative case study approach was applied in two regions per country and fieldwork research activities entailed focus group discussions, an ethnographic vignette-based survey, semi-structured interviews and participant observation. Research reports are available on https://www.baselgovernance.org/publications/.

[3] According to this strand of literature, social networks may, for example, provide functional support insofar as they may fulfil an emotional and social function (as a locus of socialisation and a source of group belonging), and/or else play an instrumental or informational role and function (for example, a specific network one can resort to in moments of need to pool resources and/or gather critical information).

[4] Social standing, status and wealth may also be a pragmatic function that a network seeks to pursue.

[5] Consult this reference for a critical review.

[6] The concept and methodology of ‘peer-driven intervention’ was first developed in the 1990s as an alternative to provider-client outreach models, to prevent the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV (Broadhead et al., 1998, also Grund, 1993).

[7] The mutual exchange of support in network settings hinges on an individual’s perception of fellow network members as being cooperative and supportive (Mitchell et al., 2014), alluding to the potential risks due to collective action and free rider problems (Mani et al., 2013).

[8] Relevant studies include Paluck (et al., 2016), Paluck and Shepherd (2012) and Kim (et al., 2015). According to those studies, for a collective social norm to change, it is proposed that individual-level normative attitudes must change first (i.e. their positive beliefs about a maladaptive practice), followed by normative attitudinal change of the group which then translates into factual collective behavioural change (Bicchieri, 2017; Mackie et al., 2015; Paluck, 2009). Alternatively, individuals as social animals are said to more likely change their normative attitudes if they perceive their peers to be undergoing normative and factual change (ibid).

[9] People tend not to take into consideration the long-term aggregated negative effects [of corruption for society] as a whole (ibid.).