Corruption risks and remedies in a crisis – insights from an ADB webinar

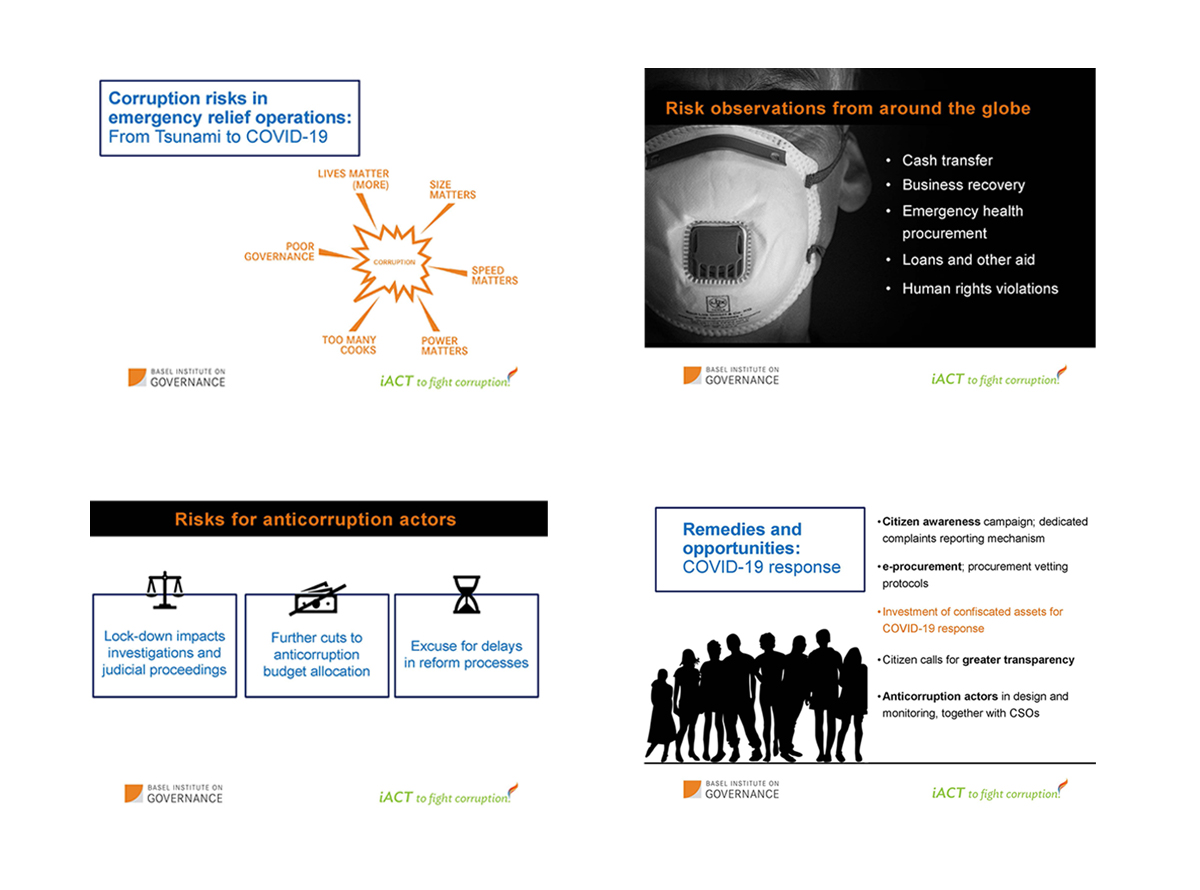

Where corruption is already rampant, a crisis makes it worse. There are flash floods of relief money landing in contexts where power is imbalanced, governance is weak and criminals already know how to game the system. But we can fight back by making anti-corruption an integral part of crisis relief efforts. Like emergencies in the past, the covid-19 pandemic demonstrates that anti-corruption is not just a nice-to-have but can really save lives.

This was the gist of a recent presentation I gave at an Innovation Speakers' Series webinar on Fighting Corruption at a Time of Crisis organised by the Asian Development Bank (ADB)'s Office of Anticorruption and Integrity and Department of Sustainable Development and Climate Change.

The webinar recording is online and the presentations by myself and my co-presenter Kelly Bird, Country Director of ADB Philippines, are available here. But since I know that snatching an hour to watch a recorded webinar is a luxury most of us do not have, I thought I’d briefly set out some of the crisis-related corruption risks and approaches I spoke about.

Some of the insights are based on my experience as former Programme Manager for the ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia-Pacific, where immediately following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami we brought together governments, the private sector and civil society to discuss how to curb corruption risks while dealing with the crisis. Other insights are drawn from the Basel Institute’s current work with governments across Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America in tackling corruption and recovering stolen assets.

The world’s most transparent donor

First, my congratulations to the Asian Development Bank for once again being named the most transparent donor organisation in the world. Beyond the accolade, this kind of achievement is already a first step in making sure that crisis relief operations are handled with great integrity.

In a natural disaster or health emergency, organisations like the ADB give large amounts of money very quickly to countries with poor governance frameworks and existing high risks of corruption. And few criminals let such an opportunity go to waste. Where systems for embezzling money from aid funds and loans exist, the emergency situation just opens the door wider. Transparency in turn opens the door to more scrutiny, and thus is a first line of defence against those who want to make a profit on the back of a crisis.

When it comes to what donors can do, coordination is another key word. During the Indian Ocean tsunami, we saw hundreds of small donors and organisations flooding in to help. This was all very welcome and well-intended, but again criminals knew how to turn a well-intended flurry of activity to their advantage. When nobody really knows where the money is coming from and where it's going, it’s hard to know that something is missing.

Politics and power imbalances

Power matters, I wrote on my first slide. What that means is that the imbalance of power can – and will - be misused to misallocate funds. When people are poor and perhaps not very literate or used to speaking up against authorities, they are hugely exposed to being the conduit to misuse of funds. If such a person is entitled to $150 in relief money and only gets $100, what can they do? And that is if they even knew they should get $150.

Information is key to create or correct power imbalances. So, again, transparency is essential, as is information. But note that information must be in a form that can be understood by those people who are targeted. This necessitates a varied approach and an understanding of local context, details which easily get lost in the middle of a crisis.

In a similar vein, politics needs to react calmly or else will make matters worse. In a situation of crisis, politicians are under pressure to act fast, to get money to the people and places that need it and show voters that they are looking after them. But erratic actions create more damage than good. So slowing down just a little bit might help save more lives than when money is dished out without the necessary controls.

No need to look hard to see the risks

It’s not hard to see the risks (and real cases) of covid-related embezzlement and price inflation, because they existed before.

People who have already stolen from procurement systems know very well how to do it, and of course find it easier when there is more money and fewer checks. Large informal economies and low penetration of formal banking also mean more risky transfers of cash and mobile money. (On this, read my colleague Andrew Dornbierer’s recent quick guide to mobile money and financial crime.)

A risk that is less discussed is the impact on anti-corruption action. Some of our partners have reported how lockdowns basically halted investigations and judicial proceedings, as well as reform processes. Others fear that the economic downturn resulting from covid-19 and the need for fast cash for emergency relief can be an excuse to cut budgets for already squeezed anti-corruption institutions and programmes. Our International Centre for Asset Recovery team debated some of these issues here.

From risks to hopes

Giving up in the face of so many risks is however not an option when lives are at stake. There is a lot we can do and it might even turn the crisis into an opportunity.

First, the lockdowns can trigger progress in implementing e-procurement and rapid procurement vetting systems, plus long overdue investments in other technology. Some countries are allowing virtual court hearings and video-taped witness statements for the first time, saving time and money in the process. Locked-down investigators are discovering the rich pool of open-source intelligence available on the internet (allow me to mention our Basel Open Intelligence tool here) and the flexibility of eLearning courses. We’ve had good experiences combining eLearning with virtual instructor-led training that we hope to carry forward into post-covid times.

Second, citizen awareness is more crucial than ever. We have been supporting journalists to help them conduct intelligent, constructive reporting on covid-related risks and corruption cases. Citizen complaints and corruption reporting mechanisms like Kenya’s anonymous whistleblowing system or Ukraine’s Business Ombudsman Council can also play a huge role.

Third, Kenya has triggered an important debate about the use of recovered stolen assets to support the covid-19 emergency response. Early in the pandemic, our partners at Kenya's Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions presented the National Treasury with a cheque for 2 billion Kenyan shillings for use in covid-19 relief. The pandemic emergency can concentrate the minds of those who are in charge of determining the use of recovered assets. And maybe this situation has made it clear: When assets are stolen, they are stolen from the people. When they come back, they should go back to the people.

The parallel is obvious: When corruption occurs in times of crisis it means lives are at stake. The deadly impact of corruption on people has never been more blatantly obvious; and suddenly corruption and money laundering are not (only) technical matters for specialists anymore. And effective corruption prevention and enforcement becomes an essential service much more than a well-sounding political commitment at times of elections.

We need to make sure that anti-corruption actors do not suffer from the crisis but, if anything, their work is given the budgetary boost and political support it requires, in or after a crisis.