Money dirtying: shining a light on how clean money turns into bribes

There’s a lot of attention to the laundering of “dirty money” – but very little about how clean money can be turned into bribes, kickbacks or payments to terrorists.

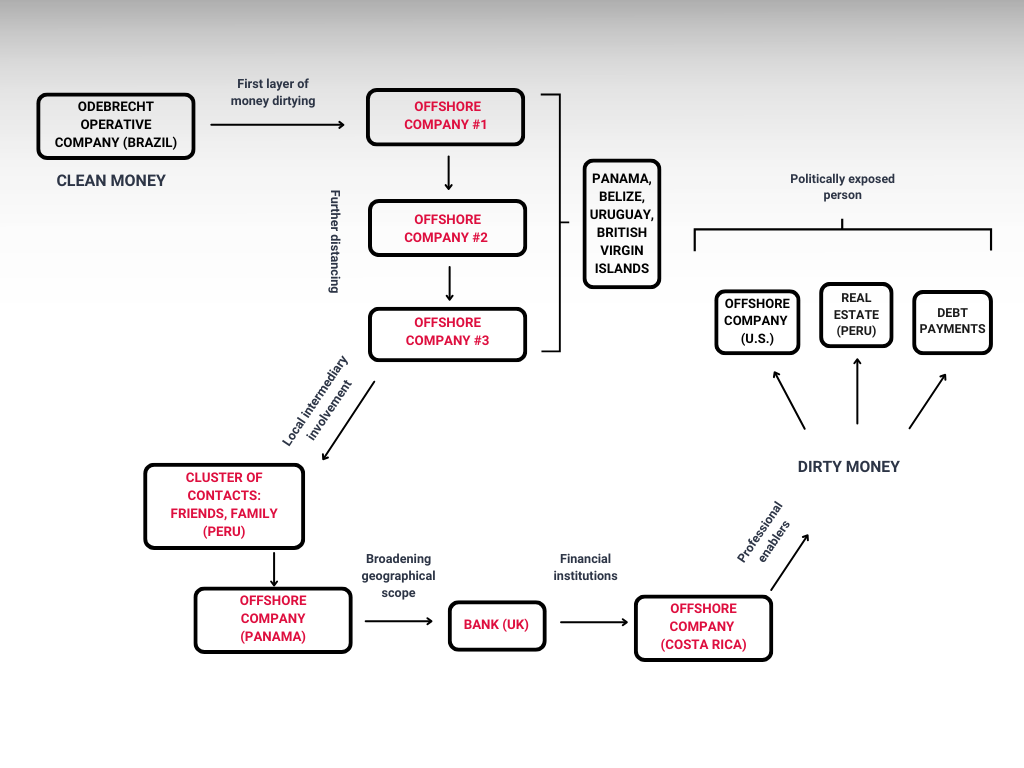

Together with David Jancsics, I examined the money-dirtying strategies at the heart of one of the world’s most dramatic corruption scandals: the Lava Jato or Car Wash case. How did the multinational company Odebrecht manage to secretly channel millions in legitimately earned funds to bribe politicians and bureaucrats across the continent? Our article Turning Legally Obtained Resources into Illegal Payments: A Money Dirtying Scheme attempts to answer this question and to explore the networks of individuals and entities that made the schemes possible.

Exploring the concept and practice of money dirtying could help practitioners get a more holistic view of major financial crime cases. It could also potentially lead to new ways to prevent, detect and intercept illicit financial flows.

What is “money dirtying”?

We use the term “money dirtying” to refer to the process by which clean, legitimate resources are turned into illicit payments used for corruption, the financing of terrorism and other illegal activities.

The term was originally coined to describe the mechanisms of terrorism financing in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, researchers worked to understand the financial structures that allowed Al-Qaeda to finance the attacks. We have repurposed the term to fit the field of corruption, but the underlying idea is the same.

What are the typical characteristics?

On the face of it, money dirtying has similar characteristics to money laundering:

- Complex, multi-layered schemes using redundant payments and fake contracts to make funds difficult to trace.

- The use of specialised professionals who can create sophisticated financial infrastructures and know all the tricks to evade detection.

- The use of informal actors such as halawadars or doleiros to escape regulatory radars.

- Often transnational, with money, resources and information shared along a cross-border network of individuals and entities.

What makes it different to money laundering?

The key differences lie in the purpose and the direction of the flow.

- Money laundering seeks to clean dirty money by reintegrating it into the legal financial system. It is a circular system, where the funds return to their point of origin.

- Money dirtying serves to transfer money undetected from the bribe giver to the bribe taker. It is linear.

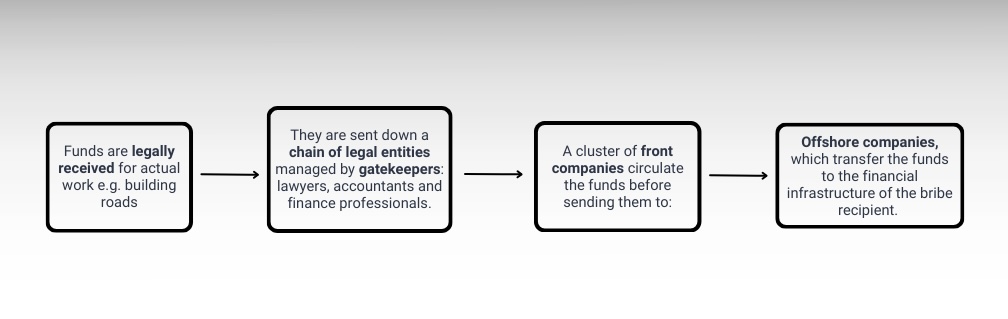

For example, in our case study, the money took the following route:

In reality, it looked more like this:

The Lava Jato case

The Lava Jato case (Operation Car Wash) was a major judicial investigation launched in Brazil in 2009. Initially focused on money laundering and illegal activities linked to a car wash company, it quickly expanded into one of the largest corruption investigations in history. By the early 2010s, investigations and plea deals had exposed the intricate financial structures and corrupt management systems of the Odebrecht Group at the heart of a web of illicit payments in countries across the region.

Unlike other cases, there is significant public information available about Lava Jato thanks to judicial investigations, journalistic work, academic studies and other reports. This allowed us to map and analyse the “money dirtying” network in detail.

The case is also an ideal case study in advanced corruption schemes. It was large, long-running and used complex, multi-layered networks that spread across the world.

Skeleton and muscles

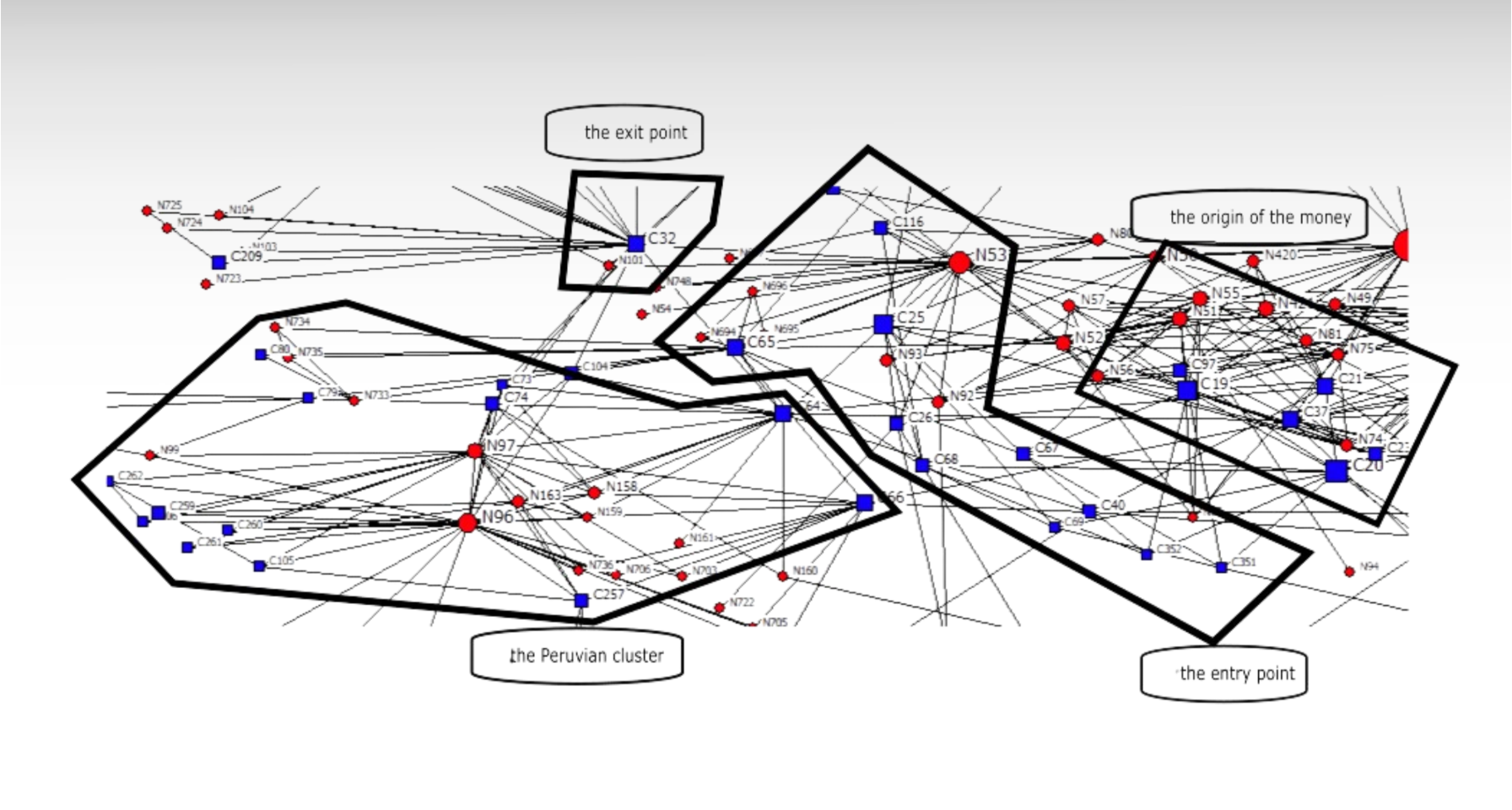

To map the complex networks of the Odebrecht Group’s money dirtying networks we looked at the data in two ways:

- We analysed the transactions, performing a social network analysis and looking at the “skeleton” of the network – how it was shaped, where transactions centred and how they moved.

- At the same time, we tried to understand the substance of the network. If you like, the muscles surrounding the skeleton. We read interviews and wiretaps, and looked at personal histories to understand the relationships between people in the network and how they operated together.

We then created a coherent framework of both the “skeleton” and “muscles”. This includes a description of each role and its function within the network.

So what?

Paying more attention to how legitimate funds are channelled towards illegal activities can help anti-corruption practitioners to gain a more holistic view of major corruption schemes.

With the increase in internal controls and regulatory scrutiny, those that engage in corruption are forced to use more sophisticated methods than just declaring bribes as “consultancy fees”, for example. A better understanding of these methods could help inform stronger internal controls and compliance systems.

This focus also helps practitioners to see how some of the same methods – legal structures in offshore financial centres, shell companies, professional enablers, informal value transfer service providers for example – can be misused not only for money laundering but for other parts of a corruption scheme.

The research also showcases the power of social network analysis in mapping the key individuals and entities involved in transforming clean money into illicit payments. Combined with evidence of their relations and interactions, this can create a valuable source of information for both law enforcement and the development of evidence-based strategies for targeting corrupt networks.

Learn more

Organisational forms of corruption networks: the Odebrecht-Toledo case

Quick Guide 4: Social network analysis in combating organised crime and trafficking