Bridging the gap: How behavioural science can strengthen anti-corruption and crime prevention

This article by Claudia Baez Camargo offers valuable insights into how behavioural science can inform more effective anti-corruption strategies and crime prevention efforts. By shedding light on key behavioural drivers and practical approaches, the piece provides a strong foundation for those seeking to better understand how human behaviour can be positively influenced to promote integrity and reduce crime.

It is republished with permission from the 7th Newsletter of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme Network of Institutes (PNI).

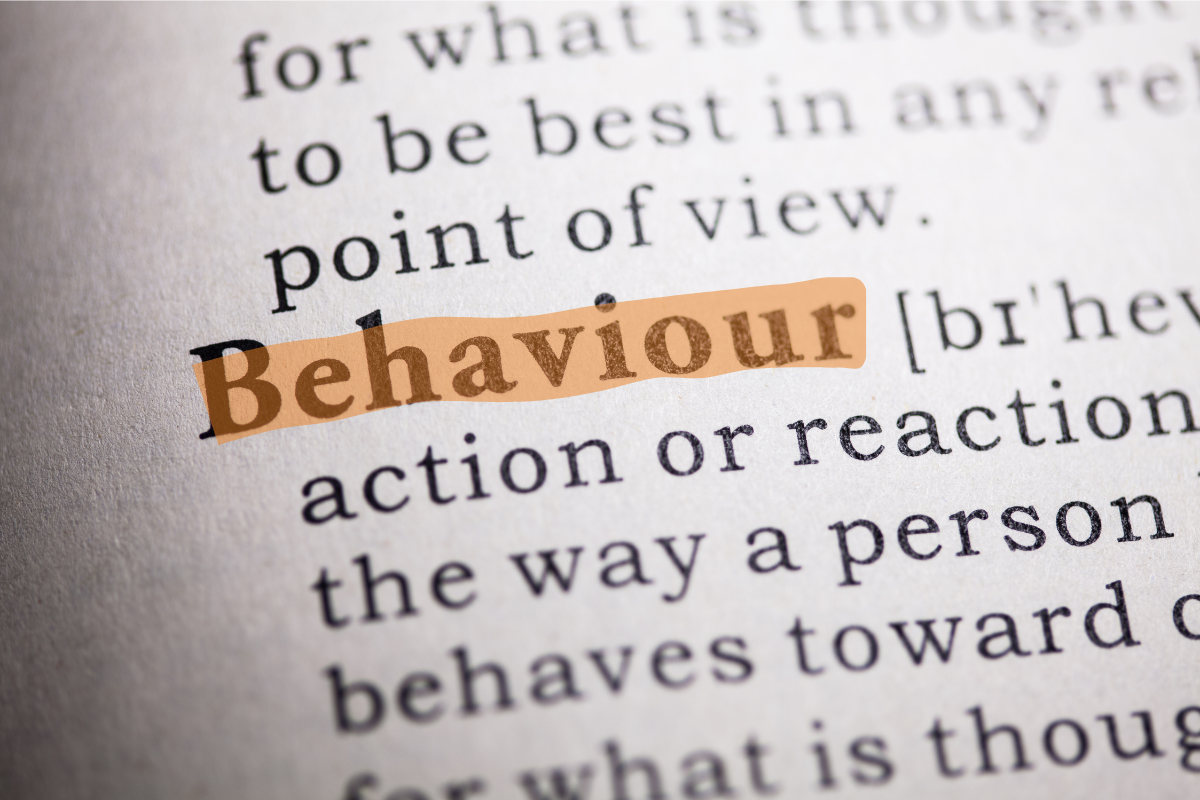

At the end of the day, it’s not formal policies and regulations that prevent crime or make criminal justice systems work better – it’s people. And people’s behaviour is shaped not just by formal rules but by informal practices and deeply embedded social norms.

That’s why understanding what drives behaviour, and how we can shift it, is essential for achieving the goals of crime prevention and criminal justice. Behavioural science offers valuable insights here. It helps us identify practical, people-centred ways to encourage integrity, accountability and participation – both individually and collectively.

This article explores how behavioural science-based approaches can contribute to preventing crime and corruption. It reviews relevant international texts and shares early findings from the Basel Institute’s promising work in Tanzania and in relation to environmental crime. While our primary focus at the Basel Institute is on anti-corruption, the insights are relevant across the broader field of crime prevention and criminal justice.

Policies often miss the human dimension

Too often, policies aimed at preventing corruption and crime look good on paper. They follow international best practices, tick all the boxes and appear technically sound. But in practice, they often fall short of delivering the desired results. This pattern is familiar across all the regions in which we work.

One reason is that many such efforts overlook the people expected to put the policies into action. Specifically, not enough attention is paid to the incentives and contextual factors that shape their behaviour. Strong formal anti-corruption or crime prevention systems matter, but they aren’t sufficient on their own. Progress depends on how individuals within these systems behave – whether or not they choose to collaborate, share information report misconduct. And that cooperation is often blocked by low levels of trust or limited experience with collaboration.

Another issue is the widespread reliance on awareness-raising campaigns. While well-intentioned, these often assume that more knowledge will lead to better choices. Yet we know from behavioural research and experience that this doesn’t hold up, particularly when it comes to corruption. People usually understand that corruption is wrong. But they may still choose not to report or resist it due to a range of behavioural and social factors: the belief that “everyone does it,” fear of retaliation, risk aversion or personal biases.

Add to that bureaucratic "sludge" – unnecessary paperwork and other frictions that make doing the right thing harder – and even the best-designed policies can lose their bite.

The upshot? If we want crime prevention and justice reforms to work in the real world, we need to go beyond rules and awareness. We need to understand the behavioural drivers behind corruption and crime. And we need to use that understanding to design smarter, more human-centred interventions that nudge people toward integrity and collaboration.

International guidance on behavioural approaches

International treaties and standards in areas like anti-corruption, crime prevention and broader development often focus on formal structures and high-level frameworks. That’s understandable: the realm of human behaviour is complex, unpredictable and deeply influenced by varying political, cultural and geographic contexts. As a result, behavioural dimensions are rarely given the attention they deserve.

Some guidance documents, however, do take a behavioural lens – though this remains the exception rather than the rule. Notably, the World Bank’s 2015 World Development Report: Mind, Society, and Behavior made a strong case for integrating behavioural insights into development work. While it didn’t focus specifically on crime or corruption, it offered valuable, practical advice on designing interventions that reflect how people actually think and behave, rather than how we assume they should.

Since then, behavioural science has gained traction in public policy. Many governments have established specialised teams to apply behavioural insights to policy challenges – from tax compliance to public health. Recognising this shift, the OECD released its Good Practice Principles for Ethical Behavioural Science in Public Policy in 2022, offering guidance on using behavioural tools in an ethical and effective manner.

Yet despite these promising developments, behavioural approaches remain underused in anti-corruption and crime prevention efforts. This is a missed opportunity, since behavioural science offers a powerful lens for understanding and addressing the real-world challenges that undermine formal systems and laws.

Promising research

Two areas in particular – healthcare and environmental protection – illustrate how tailored interventions grounded in behavioural insights can help achieve corruption or crime prevention goals. Both arise from research led by the Basel Institute.

Preventing corruption in healthcare

One of the few real-world behaviour change interventions in the anti-corruption space took place in a Tanzanian hospital. The aim of the pilot project was to curb bribery in the form of “gift giving” – i.e. small gifts to healthcare workers to generate a relationship of reciprocity and secure better or faster treatment. While framed as gestures of appreciation, such practices can create expectations and reinforce corrupt dynamics over time.

The intervention used a mix of behavioural tools: simple environmental cues like posters and desk signs reminded users of expectations around the giving of gifts, while respected staff members acted as “champions,” spreading the messages through their peer networks. In just eight weeks, the pilot recorded a 14–44 percent decrease in patients’ intentions to offer gifts, as well as more negative attitudes toward the practice and reduced beliefs in its acceptability.

The accompanying working paper, Developing Anti-corruption Interventions Addressing Social Norms, offers practical guidance for practitioners. It outlines how to identify when a behaviour change approach is appropriate, develop a theory of change and design interventions that are context-sensitive and measurable.

This pilot adds to the growing evidence on why some behavioural approaches can be effective in preventing corruption while others fall short (see more). To give a taster, some of the strategies include:

- Using environmental cues tailored to the setting.

- Providing timely resources that support integrity under pressure.

- Building trust among stakeholders to foster cooperative social norms.

- Elevating role models and champions of integrity.

Tackling environmental corruption and crime

The adaptability of behavioural science also makes it a strong tool in the fight against environmental corruption and crime. These offences often flourish in settings where red tape, weak enforcement and collusive practices are the norm. Behavioural interventions can be tailored to disrupt these patterns.

Under the Targeting Natural Resource Corruption (TNRC) project, led by WWF, we produced a series of practical guides that translate behavioural insights into conservation and anti-corruption strategies. Topics include how to reduce corruption driven by excessive bureaucracy or “sludge”, how to reduce risks of collusion in community-managed forests and how to design interventions that resonate with frontline wildlife defenders such as rangers.

Other resources and activities

At the Basel Institute, we are deeply committed to advancing the use of behavioural science in anti-corruption and broader crime prevention efforts. Our aim is not just to test promising ideas, but to rigorously examine what works, what doesn’t and – crucially – why. By sharing these insights, we hope to support practitioners around the world in adapting evidence-based behaviour change approaches to their own contexts.

In this regard, an additional valuable contribution to the field is our research report synthesising lessons from a range of anti-corruption behaviour change interventions. It explores the reasons behind both successes and failures and extracts practical recommendations.

In a nutshell, we believe that effective anti-corruption and crime prevention systems must be rooted not only in solid laws and institutions, but also in the behavioural realities of those expected to implement them. Bridging the gap between formal policy and real-world practice requires a systematic focus on social norms, decision-making dynamics and local incentives.

Our Prevention, Research and Innovation team leads this work. We support anti-corruption practitioners, development agencies and other donors across three main areas:

- Research: Conducting academically grounded studies to understand the behavioural drivers of corruption and identify promising points for interventions.

- Advisory support: Helping donors and international partners integrate behavioural insights into their anti-corruption and development programming.

- Practical guidance and mentoring: Working directly with implementers to design, test and refine behaviourally informed strategies that are tailored, measurable and feasible in the context.

By embedding behavioural science into anti-corruption and wider crime prevention efforts, we can help ensure that policies are not just well designed on paper, but embraced and enacted in practice – closing the gap between intention and impact.

***

One of the key mandates of the PNI is to disseminate and enhance knowledge on crime prevention and criminal justice. This mission is carried out actively around the world by individual PNIs through various channels, including research, publications, and capacity-building activities. A notable example of such efforts was the creation of the Justice Knowledge Centre by Gary Hill –one of the first web-based platforms dedicated to sharing information and resources on crime prevention and criminal justice.

Inspired by the spirit of such legacies and by the continuing efforts of PNIs around the world, the PNI Newsletter carries forward this knowledge-sharing mission by dedicating a section in each issue to a specific topic of relevance. Claudia's contribution is the first in this new series.