What can we learn from recent money laundering cases?

During 2018 and 2019, the world has faced serious money laundering scandals involving reputable institutions. Surprisingly, abuses of financial systems were uncovered in countries that have low risk scores in the Basel AML Index, like Estonia and Sweden.

These countries have correspondingly low risk scores in other indices that the Basel Institute uses to analyse the quality of anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) frameworks and quantify corruption, financial transparency and standards, public transparency and accountability, and legal and political risks.

Are ML/TF evaluation systems flawed?

Does this mean that systems for evaluating money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) risks – including the Basel AML Index – are fundamentally flawed or biased?

No. It does mean, however, that when using a risk assessment tool such as the Basel AML Index Expert Edition it is important to understand the methodology behind the results, what it can and cannot measure, and which indicators it relies upon.

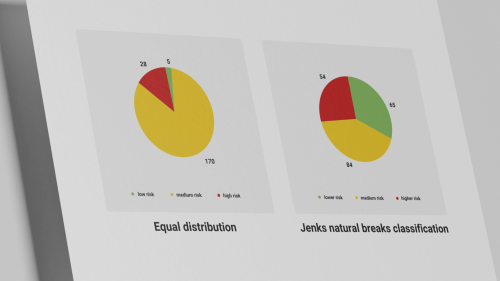

The Basel AML Index is a composite index based on 15 well-established indicators and is not anyone’s personal evaluation. If some overall scores and rankings look implausible – for example, because major money laundering scandals have occurred in supposedly low-risk countries – the key is to analyse both the indicators behind the scores and the reasons why these cases of money laundering occurred.

Tools are more powerful when users understand their limitations and not only their uses.

Red flags in addition to country risk

Tools are also more powerful when used in combination with other evidence-based tools and procedures.

An analysis of recent high-profile money laundering cases shows it is important for financial institutions and companies to check for the following red flags:

- Politically exposed persons (PEPs). Cases involving illicit money from Russia and former Soviet countries were largely connected to PEPs or powerful businesspeople with vested interests. According to media reports, for example, EUR 122 million were linked to Russian businessman Iskander Makhmudov. Viktor Yanukovych, the former Ukrainian President, funnelled a suspected bribe of EUR 3.7 million via Swedbank in 2011.

- Non-resident legal persons. It is stated that Russian and other non-Baltic customers accounted for a notably high percentage of Danske Bank’s Estonia business, through which over USD 200 billion are estimated to have been laundered between 2007 and 2015.

- Beneficial ownership and offshore jurisdictions. Shell companies are used to conceal the true nature of illicit transactions and the identities of those responsible. In the so-called Russian Laundromat scandal, to take one example of many, money entered the scheme via a set of shell companies in Russia that exist only on paper and whose ownership cannot be traced.

- Illicit trading. High-risk large transactions related to mis-invoicing and fictitious trade deals are a serious issue. Illicit trading schemes like fraudulent letters of credit, fake invoices, vessels re-routing to pick up illegal goods, and trading in non-existing goods were used frequently in the Russian Laundromat activity. These methods helped to mask movements of illicit money.

- Geographical proximity to high-risk countries. As financial crimes are global in nature and the issue of exporting corruption is now widely recognised, countries which have borders with high-risk neighbours are vulnerable to increased levels of risk. In the latest Laundromat schemes, Baltic countries served as a gateway for illicit funds from former Soviet countries to enter the Western banking system.

Measuring money laundering risks

The 8th edition of the Basel AML Index, an independent annual ranking that assesses the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) around the world, will be released on 19 August 2019.