Money laundering risks: are we paying enough attention to lawyers, accountants and others beyond the financial sector?

To explore what is holding back progress in combating money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) around the world, the 2021 Basel AML Index report examined data on money laundering vulnerabilities beyond the financial sector. Banks and other financial institutions bear the brunt of anti-money laundering AML/CFT supervision and attention, but perhaps we're missing weaknesses elsewhere?

In brief, the Basel AML Index reveals that lawyers, accountants, real estate agents, casinos, precious metal dealers, and other so-called designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) are significantly less protected against ML/TF risks than financial institutions. They also do less to contribute to anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) efforts. They should be considered a serious vulnerability in most jurisdictions’ AML/CFT framework.

We believe more supervision is urgently needed to close that gap. Extract from the full report:

Growing attention to non-financial entities exposed to ML / TF risks

A significant issue highlighted by the Basel AML Index data analysis is the generally weak application of AML/CFT preventive measures by non-financial entities – so-called designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs). A related weakness lies in their supervision.

What are DNFBPs?

DNFBPs are non-financial entities or individuals with a particular exposure to ML/TF risks due to the nature of their business. According to the FATF definition, DNFBPs include casinos; real estate agents; dealers in precious metals and precious stones; lawyers, notaries, other independent legal professionals and accountants; and trust and company service providers (TCSPs).

In an effort to support the various DNFBPs in applying a risk-based approach to AML/CFT, the FATF has issued sector-specific guidance documents for legal professionals, TCSPs, casinos and accounting professions.

In what way are DNFBPs exposed to ML/TF risks?

Traditionally, national AML / CFT policies, standards and financial supervisory bodies have focused more on financial institutions than DNFBPs. However, the latter are important players in financial and economic sectors and have clear exposure to ML/TF risks arising from tax evasion, corruption and bribery, fraud schemes, insider trading or other crimes.

To take a simple example, money launderers can buy and sell properties or precious metals to help obscure the illicit origins of their money, as one “layer” in the laundering scheme. Using corporate vehicles allows them to disguise the true ownership and control of the funds and assets – especially where beneficial ownership registers do not exist or are poorly implemented.

Moreover, there is increasing concern among regulators that some lawyers, accountants and TCSPs are advising and assisting criminal clients with hiding and laundering illicit funds, or that an accountant is used as an intermediary to avoid scrutiny from the financial institution.

Several structural factors emerge from the data that make DNFBPs particularly vulnerable to ML / TF risks, including the top three:

- A limited understanding of ML/TF risks and AML/CFT obligations

- Poor implementation of AML/CFT measures

- Weak monitoring and supervision

These are substantial problems that will need addressing to prevent DNFBPs acting as a dangerous loophole in AML/CFT systems.

Customer due diligence and AML / CFT

Customer due diligence (CDD) – knowing the identity of your customers and verifying that they really are who they say they are – is an essential aspect of identifying potential ML/TF risks. The relevant FATF Recommendations are R.10 on customer due diligence and R.22 on customer due diligence by DNFPBs. Effectiveness is measured through Immediate Outcome (IO) 4 on a risk-based approach to ML/FT prevention and reporting of suspicious transactions.

What are the requirements for customer due diligence?

CDD obligations apply to financial institutions and DNFBPs alike, for example when establishing a new business relationship, when they carry out certain transactions, and where there are doubts about previously obtained customer identification data or a direct suspicion of ML/TF. The measures cover various aspects including:

- identifying and verifying the customer;

- identifying and verifying the beneficial owner;

- understanding the purpose and intended nature of the business relationship;

- conducting ongoing due diligence and/or scrutinising transactions for consistency with the apparent customer profile.

CDD is also an important aspect of a risk-based approach to AML/CFT: where a risk assessment reveals a high risk of ML / TF, enhanced CDD should be applied to gather more information about the customer, the sources of the funds, the nature of the business relationship and the purpose of the transaction. Additional monitoring can then be applied where needed.

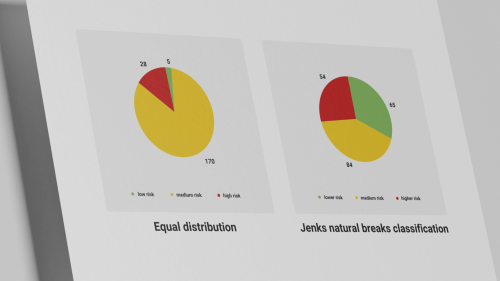

According to an analysis of FATF data relating to the relevant indicators (see above), DNFBPs have a much lower level of technical compliance with CDD requirements than financial institutions:

- 12 jurisdictions out of the 112 evaluated are rated as non-compliant in R.22 (CDD for DNFBPs). This compares with just 2 jurisdictions that are rated as non-compliant in R.10 (CDD for financial institutions).

- At the other end of the scale, only 8 jurisdictions are fully compliant with R.22, compared to 17 jurisdictions that are fully compliant with R.10.

This means that lawyers, accountants, casinos, precious metal dealers, real estate agents and other DNFBPs are significantly less protected against ML/TF risks and do less to contribute to AML/CFT efforts. They should be considered a serious vulnerability in most jurisdictions’ AML/CFT framework.

Does that mean they require greater attention and support from supervisory authorities?

Regulation and supervision of DNFBPs

In last year’s report, the Basel AML Index provided a deep dive into the quality of AML / CFT supervision. We found that supervision was generally a very weak spot in countries’ AML / CFT regime, and supervision of DNFBPs in particular.

Reviewing 2021 data on jurisdictions’ performance in FATF R.28, which sets standards for the regulation and supervision of DNFBPs, reveals that far too little has changed:

- Compliance with R.28 remains very low at 45% on average.

- 15 jurisdictions still score a radical 0% for compliance with R.28.

- Only 8 jurisdictions are fully compliant with R.28.

These figures illustrate that supervision remains one of the weakest fields in AML / CFT prevention. A 3% improvement across the board is far from the quantum shift that we would need to see.

When regulators continue to pressure financial institutions (and hopefully increasingly also DNFBPs) to do better – pressure that indeed needs to be maintained – it needs to be matched with significantly more efforts to supervise these institutions. Or else, it is highly likely that the pressure will fall short of delivering real results.

More from the Basel AML Index

- Find out about the Basel AML Index, view the latest Public ranking and find out whether your organisation is eligible for a free Expert Edition account at our brand new website: index.baselgovernance.org.

- See the Basel AML Index 2021 press release.