Why we can’t ignore fraud despite challenges in data and analysis

This article is adapted from the 2024 Basel AML Index public report.

Sound like someone you know?

The 84-year-old who lost his life savings after receiving a panicked call from someone who sounded exactly like his granddaughter, saying she was in jail for drug possession and needed USD 10,000 for bail...

The lonely widow seeking companionship online, who sent cash via a money transfer service to his long-distance love – who in actual fact was himself a victim of human trafficking, trapped in a "scam centre" on the other side of the world and defrauding hundreds simultaneously…

The small business owner who suffered reputational and financial loss after his identity was stolen and used to establish shell companies and purchase goods as part of a money laundering scheme...

The young professional, excited by the buzz around cryptocurrency, who invested USD 15,000 in an online crypto platform advertised on social media that promised guaranteed high returns – which vanished before she could withdraw them…

The government that loses billions of dollars annually to healthcare fraud, money that should be spent on some of the most vulnerable in society.

Stories of fraud and scams like those in the box above make clear the human impact of financial crime. The financial impact is no less horrifying. The UK is estimated to lose over a USD 1.5 billion annually to fraud, which makes up 40 percent of reported crime – despite significant under-reporting. Globally, individuals are estimated to lose over USD 1 trillion to online scams alone.

Whatever the real figures, that’s a lot of money that needs to be laundered on international markets.

Following our expert annual review meetings we decided to add indicators of fraud to the Basel AML Index methodology this year. This decision reflects the growing significance of fraud as a predicate offence to money laundering and as a risk that regulated entities need to consider.

Though definitions of fraud vary and data is both poor and inconsistent, the huge and rising social and economic consequences of fraud make it impossible to ignore in any money laundering risk assessment.

What is fraud?

Given the lack of a globally accepted definition of fraud, we use the term loosely as an umbrella term for activities that involve deliberate deception of an individual or entity for the sake of obtaining a financial gain. At the transnational level, fraud schemes are often orchestrated by organised criminal actors and facilitated by technology.

Fraud-related indicators in the Basel AML Index

Fraud-related data is sourced from the Global Organized Crime Index in two categories:

- “financial crimes” (covering financial fraud, tax evasion, embezzlement and misuse of funds); and

- “cyber-dependent crimes” (including malware, hacking, ransomware and cryptocurrency fraud).

It is not possible to disaggregate the data.

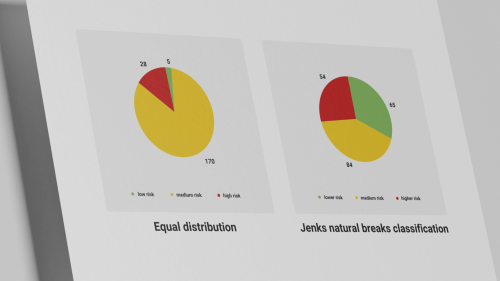

Both indicators join indicators of corruption and bribery in Domain 2 of the Basel AML Index methodology, with a weighting of 5 percent and 2.5 percent respectively. The weight of the domain (its impact on the overall Basel AML Index score) has increased from 10 percent to 17.5 percent.

What impact has the inclusion of these new indicators had?

Globally, the average risk score in Domain 2 on corruption and fraud has increased from 5.02 in 2023 to 5.12 this year following the addition of the fraud indicators. This increase may be influenced by this year’s larger country coverage, as well as by changes in performance in the existing indicators of corruption and bribery. A few highlights:

- Just under half of the countries covered – 44 percent – have a higher risk score in Domain 2. These include high-income countries and those with large financial centres. The top five from highest to lowest increase are: New Zealand (which nearly tripled its risk score), Switzerland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden. Most of these countries still have lower than average scores for corruption and bribery, but their relative wealth makes them targets for fraud, cybercrimes and the related financial crimes measured by the new indicators.

- Around 50 percent get a lower risk score in Domain 2 as a result of adding the two new indicators, though the impact is less drastic than for those with an increased risk score. The top five include, from biggest to smallest reduction, Antigua and Barbuda, Chad, Barbados, Central African Republic and Republic of the Congo.

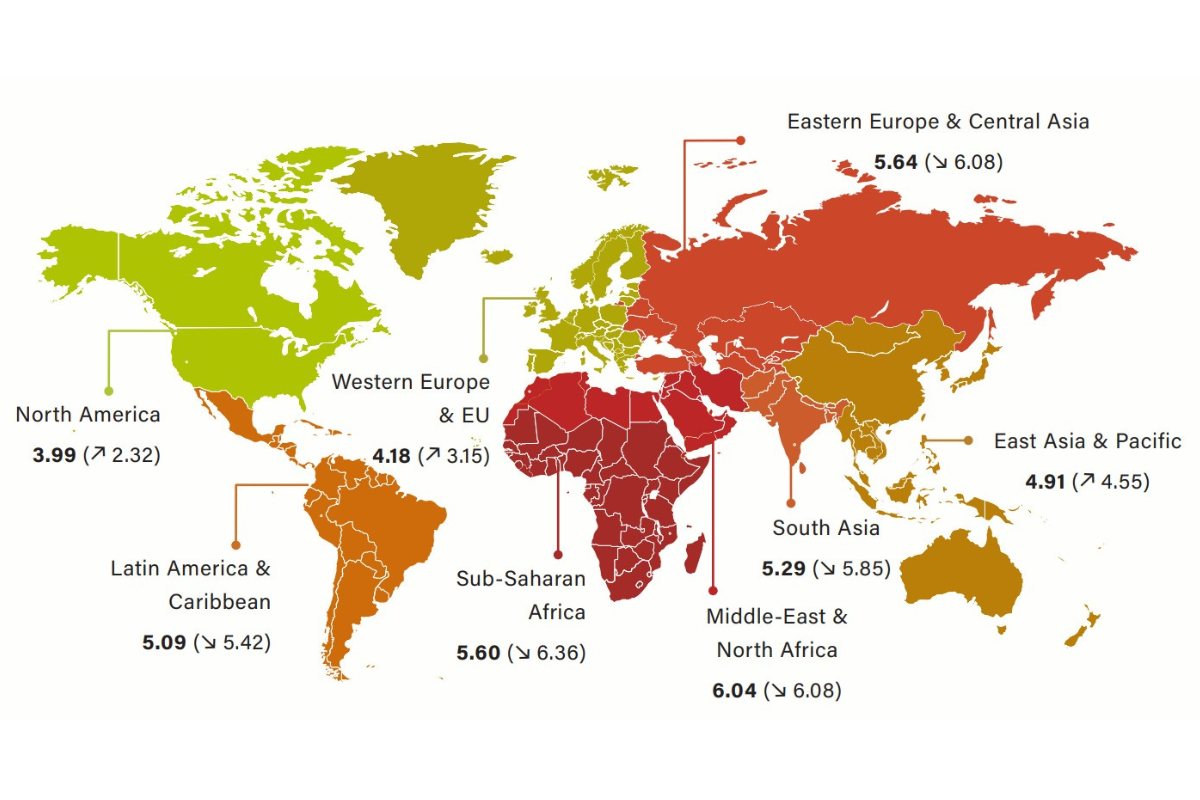

- At the regional level, the European Union and Western Europe, North America and East Asia and Pacific saw an increase in risk scores in Domain 2 while Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa saw a decrease overall. The impact on the Middle East and North Africa was negligible. This means the gap between regions is decreasing, at least in relation to performance in Domain 2.

The following map shows the regional scores in Domain 2 (“corruption and fraud risks”) after adding fraud data in 2024 (compared to 2023):

Challenges in fraud data and analysis

The reason we don’t provide more analysis of the impact of fraud data is that there are significant challenges and concerns around the quality of fraud data generally.

First, there are no globally recognised or unified approaches to collecting data on fraud. Data is mostly collected (if at all) at the country level and according to different definitions and scopes, for example with a focus on scams. Underreporting of fraud, perhaps due to feelings of shame or the desire among businesses to avoid reputational damage, is also a major issue.

As supported by an extensive UNODC report on organised fraud, a global standard and collaborative efforts to improve data collection, quality and sharing are urgently needed as the foundations of any coherent attempt to prevent and counter fraud.

Second, the cross-border nature of many forms of fraud and money laundering make it particularly challenging to assign risks to a particular jurisdiction.

An investment fraud scheme may be perpetrated in several financial centres, masterminded by a transnational organised crime group and carried out by individuals working in scam centres such as those rapidly emerging in Southeast Asia. The proceeds may be laundered across multiple jurisdictions and through the crypto ecosystem before ending up in a bank account or real estate – perhaps even in the country in which it was stolen.

Given the above challenges, and until standards and data are improved, we would urge all users of the Basel AML Index to consult the detailed breakdown of indicators available in the Expert Edition and to seek additional sources of data on specific fraud risks where this element is included in a risk assessment.

As a reminder, we provide free access to the Expert Edition for most organisations outside the private sector.

Learn more

- Read the 13th annual Public Edition report of the Basel AML Index.

- Explore the Basel AML Index.